Hiding from the algorithm

Every day the number of decisions we make that are influenced by algorithms grows. For anyone that uses search, Instagram, Facebook, or most major online retail platforms we are presented with stuff (ideas, products, memes) that represent our worldview, showcasing things that we will want to purchase, articles that will make us want to rage post or ideas that align with our world view to make us feel comfortable and content.

Algorithms are increasingly defining what we see and what we aspire to like.

This is not entirely bad, when we know what we want (or in its vicinity), a retailer revealing similar products, or getting us to the thing that we’ve been searching for when we don’t have the right language to seek it is incredibly helpful.

But if you think about platforms like TikTok as being fundamentally incremental in their design, built with the remix in mind for creators (if I see another person doing the dance to Louis Theroux’s rap, I may have to delete the app).

An article in The Atlantic describes this shift, saying that people interact more with their own content and the For You page, than with each other:

“This setup has a natural outcome: As soon as content about some specific thing—or some specific person—trends, more content of that type will be produced. TikTok doesn’t want you to comment on someone else’s video. It wants you to make your own version of the same thing. Then your version might worm its way into the algorithmically generated “For You” feeds of other users and find its own success.”

It’s this kind of thinking that is leeching its way into other aspects of creativity, leading to incrementalism when it comes to taste and aesthetic design, it’s leading us towards a bland landscape of monotony, where nothing is designed to provoke, challenge, upset or inspire.

New ideas often start from a point of disgust or horror. Even Picasso’s work was once described as “degenerate,” “odd,” and a product of “diseased nerves.”

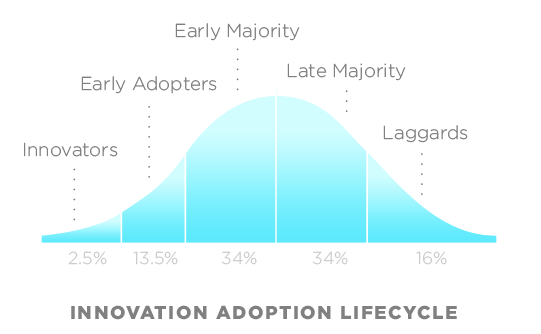

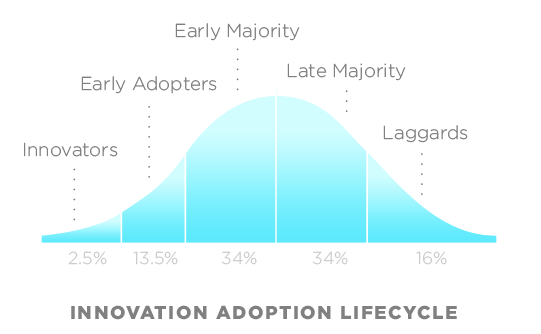

Disgust is an integral element of the cycle of trend adoption – often what happens when we initially see something new is that we experience aversion when we see it for the first time, curiosity after the a few times, and then desire later on – how quickly that happens for an individual depends on where they live on the trend cycle.

algorithmic culture trades intermittent greatness for consistent mediocrity

— Kyle Chayka (@chaykak) March 18, 2022

It’s even changing how we understand language, with words that are linked to challenging topics down ranked on the clock app (TikTok), leading to new words that allow creators to get around censorship.

I just finished reading The Candy House, the new fictional book written by Jennifer Egan about a dystopian version of the world a few years from now, where people upload their memories to the cloud, like a souped up social media platform. The world that she describes fundamentally feels like a potential direction of travel for the near future, where instead of putting on a VR headset to play a game or watch an entertainment experience, we can experience the world through someone else’s perspective. With each experience becoming a data point that can be sold, shared or exchanged.

While there has been an awareness that the filter bubble has been driving increased division through society for the past couple of election cycles, it hasn’t really transitioned into any real change. There are now increasing signs that some countries and individuals are starting to understand that everything that they put onto the internet is a data point that advertisers and social platforms can use as a means to target you with ads or content that will either keep you hooked into their platforms or shopping for new items.

One big driver of public awareness around this was Apple’s recently updated privacy strategy, something that is predicted to cost US$16bn in lost revenue in 2022, as it impacts the ability for social platforms to serve personalised ads to users.

Similarly, privacy-focused search engine DuckDuckGo witnessed an almost 50% uplift in the number of users in 2021 (but still only holds a tiny volume of overall market share with 2.53% of searches, putting it fourth behind Google, Bing and Yahoo).

Politico recently reported that the UK’s Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, Nadine Dorries arrived at a meeting with Microsoft and asked when they were going to get rid of algorithms. While it’s clear that this particular horse has already bolted, new consumer interests are emerging around what people keep for themselves, what they share and what kinds of recommendations they’re seeking.

The writer Brandon Taylor recently questioned the motivations behind sharing anything at all, wanting to keep his preferences, tastes and sources for himself (and to avoid becoming part of a trend, for which I am deeply sorry for including him in here).

“Like, there must be some way to share what I am thinking and feeling and watching and enjoying with everyone in a way that does not attempt to replicate my preferences into a trend. There must be some way of sharing that does not machine down my experience into the cuboids of digital life. My quick solution is simply to share and not identify. To focus my sharing on the moment, the instant, the thing I am looking at and to discuss it as a local phenomenon. Rather than to identify it for the marketplace. I am still thinking about it.”

Finding inspiration outside the algorithm is driving the creation of new services like the newsletter Perfectly Imperfect. Co-founder Tyler Bainbridge says of the service:

“These days, it’s so easy to stay in your own hyper-personalized algorithm bubbles and just throw on whatever Netflix thinks you’ll like, or buy the rug Instagram keeps putting on your feed. So we think it’s pivotal to break out of your day-to-day autopilot and challenge yourself to try something different.”

Other personal curation platforms I love include Collagerie, which was founded by ex British Vogue fashion editor Lucinda Chambers, whose taste I adore, Blackbird Spyplane, and Australian app Her Black Book (a product I helped build the pre-launch strategy for, and which seems to be going really well).

Things to consider

What is your balance between iteration vs innovation, and what does that mean for creative teams?

How much (if any) discomfort are you willing to expose your customer to?

Where can algorithmic strategies best serve the business in a way that is meaningful to customers

Where can human curation help consumers find the correct item?

If you’d like to discuss how to implement more human-focused curation strategies, then feel free to get in touch: hello@futurenarrative.com