The death of trends

The Discourse seems to have caught wind of the trend universe, with a sudden and very intense obsession with trends, naming them and, of course, their death.

There is some truth to this, with the rise of sites like Aesthetics Wiki documenting the breakdown of mainstream culture with the rise of micro-cultures that disappear almost as quickly as they emerge.

The breakdown of mainstream culture is taking on other forms, from the lack of “original” blockbuster movies (the ones that do big numbers tend to be sequels), and music (shut up and play the hits).

In this, some of the shifts are good, away from an imposed sense of what is cool, to a multitude of self-defining sub-cultures deciding what is cool for themselves. As aspiration becomes decentralised, trends become increasingly chaotic and fragmented. On the negative side, it means people are losing a common language and a means of connecting with each other. All of this is making life harder for brands, used to creating a story that is designed with “everyone” in mind.

While mainstream culture is fragmenting, people are seeking a sense of cohesion and conformity among the groups that they choose to be a part of.

“Thus: Dance challenges are A Thing. Digital blackface is A Thing. Slugging is A Thing. Celibacy TikTok is A Thing. Cryptocurrency is A Thing. NFTs are A Thing. The metaverse is A Thing. Pandemic brain is A Thing. The Great Resignation is A Thing. Being woke is A Thing. BIPOC is A Thing. Cancel culture is A Thing. Podcasting is A Thing. Wordle is A Thing. Vibes are A Thing. Everything is A Thing. Nothing is A Thing.” The Age of Everything Culture Is Here

One of the commonly accepted truisms about Generation Z (particularly in the insights world) is that they are all unique. There is some truth to this, when it comes to sexual, gender and racial identity, this generation is the most diverse and accepting of their diversity.

But when it comes to beliefs and taste, belonging and fitting in has never been more important. You see this in conformist behaviours when it comes to the fear of cancellation, and concerns about how they are portrayed and perceived. (Research in the US found 45% of working people under the age of 30 were afraid of losing their jobs because “someone misunderstands something you have said or done, takes it out of context, or posts something from your past online” and Squarespace/Harris Research found 60% of Gen Z and 62% of Millennials think how you present yourself online is more important than how you present yourself in-person.)

We are also seeing it in the emerging shift towards TikTok analysts attempting to name things, (something I’ve been talking a lot about with clients and at events), with the rise of ever more niche (and sometimes ridiculous) trends.

When something has a name, it can be categorised and logged somewhere, neatly boxed away in a person’s mind. When we do this with people and ideas we are looking to impose order on the world (this person is like us/not like us), giving us a framework within which to interact.

In a world that feels increasingly incomprehensible (BANI), being able to organise the world makes us feel safe, and allowing people to find and create new, ever-more niche subcultures. And the internet means that people who might previously been outliers in a location can find critical mass via social platforms, connecting and forming connections with other people who love the same things that they love.

So what does that mean for brands?

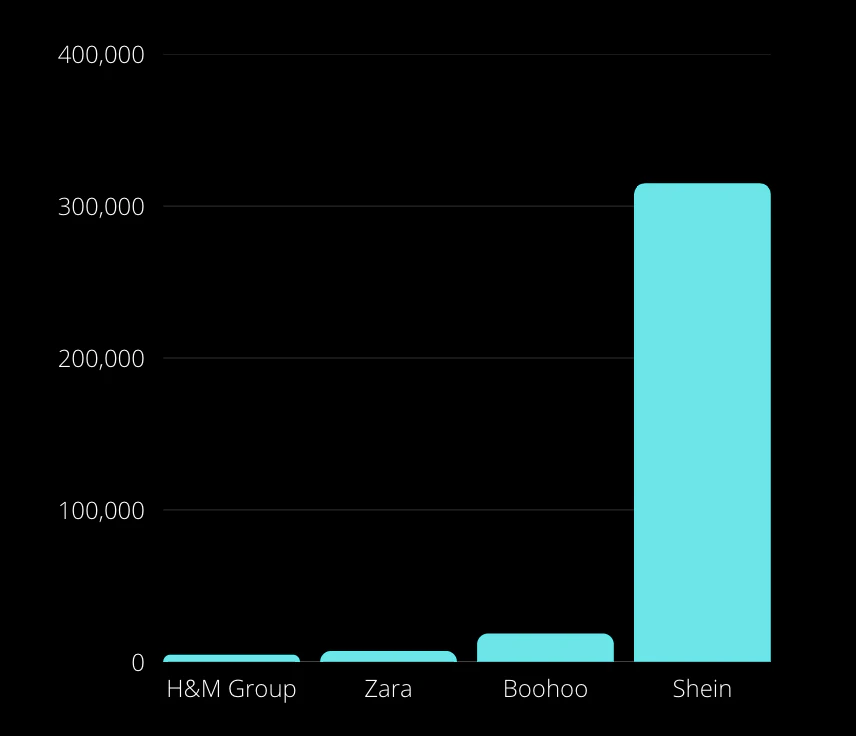

Trend-focused brands have increasingly been taking a test and learn strategy when it comes to product, ordering smaller and smaller volumes in increasingly large numbers of styles in order to see what sticks. The graph below, created using Edited data, highlights how ever-faster fashion brands are using this kind of strategy. This was the number of new products released by the leading fast fashion retailers between January and April (Shein released 314,887 items, versus 4,414 at H&M Group in the same period). This pace of creation is leading to significant quality issues (this TikTok video is both amusing and devastating).

For brands looking to create deeper social and cultural resonance, this strategy leaves much to be desired, as these brands are only engaging only on a very superficial level, and are treated by the consumer like commodities, bought cheaply, worn briefly, then thrown away.

As the trend cycle moves faster, products are commodities, and it’s not enough to differentiate on product alone. Creativity in product (unless it is shrouded in patents) is not an own-able platform, the differentiator is the story you tell about the products you sell.

Understanding the product trend cycle, but not being a slave to it, is key for brands looking to move beyond commodity perception. Connecting with culture and community have never been more important.

In an interview I did recently with Nick Benson, the founder of beauty manufacturing network Atelier, he said: “The era of the 10 billion dollar beauty brand is over – we’re now moving into a time when we’ll have a lot of $10-100m brands serving smaller communities, and serving them really well. We’re about to enter a golden age of consumer packaged goods (CPG) where people are getting more of what they need, without having to compromise on their identity or how they represent themselves through product.”

Brands that epitomise this shift include Sports Banger – a Tottenham-based streetwear brand that taps into rave culture to create a brand that has developed social resonance beyond the subculture it was initially designed to serve. Jonny Banger, the brand’s founder, started out as a bootlegger, and has since partnered with some of the brands he used to rip off. But beyond this, the brand’s resonance extended beyond London ravers when he sold highly-coveted NHS/Nike T-shirts and hoodies through the worst days of the pandemic. The profits were used to feed local doctors and nurses (and support local food businesses). He also encouraged local children to draw on letters sent by the UK Prime Minister, which were then displayed in a London gallery, and turned into a book. (Read more on this here, it’s worth your time.)

Bode is another brand that moves beyond commodity status with products and stores that can’t be easily replicated, through its use of incredibly labour-intensive craft and one-of-a-kind products. The jacket below is a historical reproduction of an antique quilt block from around 1930. It is quilted and made from thousands of pieces of scrap fabric, where no square is larger than a postage stamp.

Elsewhere…

Deciding whether I’ll be up early to score a pair of the Tom Sachs Nikecraft General Purpose Shoe (GPS) “Boring” sneakers tomorrow. What I love about them is how they’re designed to remind us that “beauty comes in creating connection with the things one owns”, that by tearing, staining and repairing them, they become unique (and more valuable). This tracks quite nicely into these ideas of de-commodifying the product ownership experience (and everything I wrote here in the Evening Standard about living more sustainably). Newer is not always better.

Maximalism moves us away from the languishing of the past few years and makes us feel something , be it wonder, joy or even disgust. “Where good taste is demure, bad taste is bawdy. Where good taste is minimalist, bad taste is maximalist. Where good taste whispers, bad taste screams: “Look! React! Feel!”

She Invented Adulting. Her Life Fell Apart. She Wants You to Know That’s Okay.

‘Crypto Ruined My Life’: The Mental Health Crisis Hitting Bitcoin Investors

Main character energy is still going strong: The Mundane Thrill of ‘Romanticizing Your Life’

Outside of the speaking at conferences part of my work, I often get asked, ‘what is it that you do exactly??” Here’s a good primer. Futures work can take many forms, from understanding how lifestyles will change in order to help a supermarket operator create the right kinds of stores over the next decade, or understanding how attitudes to sustainability and value are likely to evolve, so brands can tell the right stories and build profitable products. And other days it means working to help suppliers understand what kind of holiday decorations will have the greatest resonance.